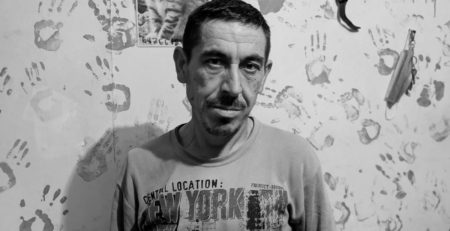

Valbona Azizi

The interviewer: Okay. Welcome to this interview and thank you for agreeing to be interviewed. As I explained to you, you have to talk about your experience as a refugee. We could start with when the war started. Where were you, who were you with, and what do you remember?

Valbona Azizi: Thank you. It is my pleasure to talk all about it because it was a really difficult situation. Maybe the fact that my children were little made the whole situation more difficult for me because I was worried more about them than myself. I was young, around 30. I mean I had a life, I was happy with my children and it all turned down at once. It was hard for me to face the reality and what was going on. Also, my children were little, they were in diapers, and I was scared because they were used to playing with toys and going out and… they had a different life and we had to isolate ourselves in the house all at once. We also covered the windows with thick blankets so they wouldn’t see us, and they wouldn’t see the lights on. I had to play with my children the whole time and had to tell them to stay quiet. It felt like they were grown-ups because they stayed quiet. They would observe us and listen to what we were talking about. It was like they understood what was going on. Everything changed all at once. Before that period, they would scream and ask for things, they would cry because they were free. And that’s why it felt like they understood they shouldn’t ask for a thing. They kept quiet. We listened to the news. The war had started and the attacks on Adem Jashari’s family had started. It was a breakdown because we didn’t know what was going on and we didn’t know how to protect ourselves. The news was terrible. I know my father-in-law always put the channel “Europa e Lire” on the radio because those journalists reported more detailed information than those on the television. Your head was all messed up and you didn’t know what would happen. I remember my mother came. She had locked the house because she was alone and she came to ours. She brought three bags of food. I asked her what was all that. She asked me whether I had listened to the news and she told me we won’t be able to go out. She told me there were too many policemen on the way she got there and in front of the house – our house was close to the small post office in the city. In front of the post office were a big tank and a pinzgauer from which you could only see the barrel. They would turn around the barrel. My mother told me they were close to shooting here. Oh Gog, and…

The interviewer: Did you see such tanks?

Valbona Azizi: Yes. On the following day, as my mother was tired and lied down, she mentioned that she had forgotten to buy Prolom water. She drank that kind of water. So, I said, oh I would go and buy her some. I didn’t tell anyone. The children were sleeping so I went to buy some water for my mother. I walked on the main street and I saw a big tank with that kind of barrel. They would follow me as I walked. I was feeling brave at that moment and I wanted to go and buy the water even if they shot me. I went in and bought 6 bottles or how many there were left in the stole. The owner of the store told me to hurry up and pointed to pinzgauer. He told me to hurry because he was closing the store. I got confused and wanted to see if we needed anything else but he didn’t let me. I didn’t pay for the water, he only told me to hurry. I got the water and started walking home. I had to walk up the road and I waited for them to shoot me. But, fortunately, I got home. I saw them all sitting and listening to the radio. We also heard stories from people about how they maltreated them and how they took their stuff. We heard that the police had gotten into the houses down the street as they were eating their meal. They left their plates as they were because they told them to run off. The mean of the neighborhood got all together because that neighborhood was like isolated, and they discussed what to do; whether it was better to leave before the police came or leave with only our clothes on when they’d come. When my husband got home he told us they decided to leave – some would leave by car, some others by tractor, and they were all organized to take also the ones who didn’t have cars. So, everyone would take someone. They were all set. But, in the evening, we got informed that nobody was able to pass through the city because the police were at the main roundabout and wouldn’t let anyone pass; they were maltreating people and would take their possessions. They beat people on the street, took their money, and maltreated them. When people saw what was going on there they tried to escape through other streets. But, the police were everywhere and they beat, maltreated, and took the money and the possessions of anyone they caught – they also took their cars if they had one. So, we decided not to leave by car but to go on foot and then get on a train. We knew people were leaving and running off by train. And that’s what we decided to do. I had a small bad and I took some things for my children. I didn’t take a single thing for myself or my husband, I only got clothes for my children. I also took some chicken pate and biscuits. I got a jar of honey even though I had doubts if it would get broken and it would stain all the clothes. But, I wrapped it and I thought we would at least have some honey on the way there because you didn’t know what would happen. We woke up early. I dressed up the kids – my oldest, Joni, was 5 years old and he said “why are you putting me these nice clothes on?” – I told him we were going to Donat’s. Donat was my aunt’s son but he was the same age as my son. My aunt used to call me on the phone and invited me to Gostivar because her husband was from Gostivar. She asked me to go there because of the war in Prishtina. I didn’t believe that the war would start. So Jon was happy to go to Donat’s. When we went out he saw the whole neighborhood because everyone was ready to leave and they were carrying all those who were sick and old. So, he said “Are they all coming to Donat’s?” – I told him no, they were going somewhere else, but we were going to Donat’s. And I asked him not to speak. We locked the house and started walking…

The interviewer: Did you walk to the train station?

Valbona Azizi: Yes, we were on foot but we were all helping each other. Young boys would help others with the bags or they carried the children. Everybody was doing something and they all tried to help each other to make all that easier… three old men were in wheelchairs. We had to push them. When we got to the main street, I remember that from Qerim until all down seemed all black. The road was full of people in the middle, and on the pavement were 10 or 20 Serbian policemen in a group. We walked down there. They didn’t do anything while we were walking, they were only observing. We walked just like soldiers and it was quite far away, I don’t know how many kilometers, but it was Fushe Kosove – Prishtine – Fushe Kosove. We arrived at the train station. The train got there and we tried to get on the train. People were all pushing because the train was small in comparison to the great number of people there. I remember my mother gave Jeton a cap that elderly people used to wear and put him in the train cabin. She told him to act like stupid and like he had mental disabilities. He put on the cap. Another neighbor, Visar, was a tall and good-looking boy. He was wearing a jacket and my mother asked him why was he dressed like going to a wedding; he told her to go change into some ripped clothes. So, yeah, we got on a train. The police got there. He was acting kind, he told us that in Bllaca the whole land was mined and that we had to walk through the railway when we would get off the train. He was acting like he felt sorry for us but that he had to do his duty. That was his explanation. Along the road, Roma children threw rocks, mud, and everything they had on the train.

The interviewer: So, you got on the train and arrived in Bllaca.

Valbona Azizi: We arrived in Bllaca and…

The interviewer: Can you describe how did Bllaca look like?

Valbona Azizi: Yes, I can describe it quite well. It was a true hell and I saw people all covered in mud and they were not even staying in tents. Because, if you stay in a tent you at least have a place to sit, but those tents were made of nylon. People had built them with what they had – to only have a place to put their head because their body was all out. It was all mud because it had rained. My father-in-law saw a field over there somewhere and he said do not rush to stay here in the mud but let’s move to the field where the grass was clean. But, we first wanted to try to get on the road. Up the road, you could see stopped cars. But, we wanted to try if they’d let us, if not we would return back on that field. We went there through the crowd. I saw people who had stayed there for three or four days and I don’t know how they could stay there. When we arrived there the Macedonian police had put the ramps and said *speaks in another language*. I guess we were lucky they told Macedonians to let people pass at that moment, we gave them some money – to a young soldier – because you couldn’t give money to anyone. He said yes and opened the ramp and we got on… there were 100 buses a day to take people from Bllaca. They took us…

The interviewer: Did you know where they were taking you?

Valbona Azizi: No, no. It felt like when the shepherd brought the sheep out. They would tell us where to stay and walk, we didn’t know where we were going. When we got on the bus, we were already all in mud until we got onto the main road. I told the driver if he could stop me in Skopje because I had my uncle there. He told me he couldn’t do that, and they couldn’t let us go. He told us they would take us to a place and told us we were free and safe, and we didn’t have that police anymore, but he wasn’t allowed to let us get off the bus.

The interviewer: Where did they take you?

Valbona Azizi: They took us to Stankovec. The American soldiers and all KFOR and NATO were building tents all day and night. To make a place for us. We stayed in Stankovec for a night. They brought us diapers, which I couldn’t buy back in Prishtina because they were expensive, and they also brought us tinned food, bread, water, and everything. It was a bit of a problem using WC because they had just made them. But, it was just one night there. On the following day, some relatives came to pick us up and took us to the station. I asked them to take me to the bus station because I had a place to go. They took us to the bus station in two cars. They asked us if we needed anything and we told them that we didn’t. We didn’t even have money. My neighbor who was with us said we should first sit there somewhere. We stopped there and ate some kebabs. When I sometimes think about the whole thing and the situation we went through in Prishtina… but we were hungry. We ate and then got on a bus to go to Gostivar. My aunt lived in Gostivar. Her husband had found a house for us – they had told the man that someone was coming with her family and neighbors – and they gave us the house immediately, without any troubles. We got settled there. They were working in Switzerland and had left their house and everything there. It was all dusty and the batteries and the water didn’t work. But, my husband was an electrician and he fixed it. We went out and bought the stuff we needed. There were some souvenirs in that house and since my children were little I was afraid they’d break them. I told the woman to keep a room locked and put the souvenirs in there… but she said it’s fine, there’s no need to because they’re just kids, they can break them all. They were all so kind. Later on, they told us there was a place where you could go with your own pot and ask for food for the number of family members you had – pieces of meat, beans, mashed potatoes, boiled cabbage, goulash, potatoes… You had different dishes so you had to take your pot and go get food because we didn’t have money.

The interviewer: What about clothing?

Valbona Azizi: That was a big problem because I didn’t take anything for myself or my husband with me. We only had those one set of clothes we were wearing from the beginning. I only took a bag with the clothes of my children. The weather started getting warmer, it was April 7th, 8th, and 9th. I was in my sweatpants. I asked the woman there because I had never been to Gostivar and I didn’t know if they had a flea market and I told her my problem. We went there. I don’t know where I got the money, I can’t remember. I guess it was my husband’s cousin. He was living abroad and asked us if we had money and we told him we didn’t. So, he gave us some money and the owner of the house as well because all the money we had we gave to the police and he let us pass. Then I went to the market as I wanted to buy something with short sleeves. But, the woman, the daughter of the owner of the house, told me it was embarrassing to do so because I was still like a bride. She told me to get something with long sleeves…

The interviewer: under the elbows…

Valbona Azizi: Yes, under the elbows… I asked her what about shorts – she told me no. So, I bought some long pants but they weren’t thick. However, that was all good for me. Then… despite the dishes we got there, they told us we could go get charity help if we didn’t like the dish. The woman told us where the place was. It was like a store where we could go and take stuff. They had everything, like clothing, leggings for children, pajamas, and everything you wanted for your children. Sweatpants also, and hats. When I got to the other side… it wasn’t a big problem to get clothes for my children because I got some pairs from home for them and I could wash them, put them to try, and put them on again. The main problem was that I didn’t have anything for myself. On the other side of the store, I found clothes for adults. I got some sweatpants, pants, and other stuff with long sleeves because that’s how it was. They didn’t call me by my name but by my husband’s name. That didn’t bother me because they left us their house and invited us to lunch because we were refugees from Kosovo. That meant a lot to me. They were so welcoming. I had everything there. Then, we would go get eggs, cheese, meat…

The interviewer: You cooked at home…

Valbona Azizi: Yes, because we had the kitchen and all the pots from Switzerland. You then felt bad to go and get lunch … even if you did, but like for breakfast children wouldn’t eat those things. But when we went to that charity help center you could fill your carriage just like in the shops nowadays with anything you need. So when you take those things…

The interviewer: You stayed in Gostivar for 3 months?

Valbona Azizi: Yes… it was less than 3 months, around 2 months. Another important thing to mention is that we didn’t have our IDs with us. As refugees, we had to wake up at 5 and go wait in line – but when it was my turn they closed it because they got tired working. There were all refugees… we had to go there again. We had a hard time getting them, the pictures and the name details, the fingerprints… After we got them, when I looked at them I saw that they were valid until June 30th. I told my husband that we had a hard time getting these IDs but they are not valid for too long… it was already May – so it was valid for 1 month. That’s when I came to see that it was all set…

The interviewer: Everything will come to an end…

Valbona Azizi: we will return to Prishtina sometime in June…

The interviewer: Do you remember what was Prishtina like when you returned?

Valbona Azizi: From the car… when we passed the border and got to Kosovo you could see the houses pricked by the bullets, nobody was on the streets, and the grass looked like nobody was there for 10 years and not only 1 month. A complete demolition. When we got to Prishtina it was a little different because it was the time the Serbian Forces moved back. We returned because they had signed the Agreement… the Serbian Forces had to move out until the 21st. We set off from Macedonia on the 23rd. Whoever had planned to return did it immediately on the following day. Before the Serbian Forces moved out on the 13th. But, since my children were little I didn’t want to return just yet because we didn’t know where we would go. We took some products from the charity services… we got 4 bags of American flour. We wondered why would we need 4 bags, but they told us that you never know. We didn’t know where we would go… Fortunately, our house wasn’t burnt. Someone was there… Albanians stayed there, also some Serbians. They had gotten there and taken stuff but those were not valuable. The most important thing was that the house wasn’t damaged. Other people would tell stories about how they found their damaged houses and ripped off the sofas and different stuff. At my parents’ house, for example, they had written on the wall with ketchup. They had unplugged the fridge, maybe the power had gone off, but you could feel the odor of the rotten food. It was terrible. There were only some small things in our house, nothing big. Then we started going back to our routines. We had flour, salt… we had troubles with electricity after the war because they’d cut it off. It was a big deal turning on the washing machine because the power and water would be off. There was only a short period when you had both the power and water on.

The interviewer: to turn it on…

Valbona Azizi: I would first fill a bucket with water and when the water was on the power went off for 2 hours. I had to rush to turn on the washing machine and I put water into the washing machine from the bucket until the other step of the washing program. And then the spin-dry process would be turned on at the time when both the water and power were on.

The interviewer: Thank you very much!