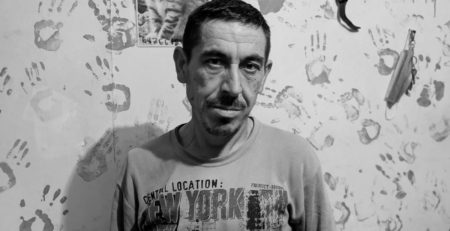

Daut Qulangjiu

Bjeshka Guri (interviewer)

Daut Qulangjiu (interviewee)

Acronyms: BG=Bjeshka Guri, DQ= Daut Qulangjiu

DQ: I am Daut Qylagjiu. I am the Romani program editor in Kosovo’s public television. I have been working as a journalist since 20002, I started working as a journalist in a radio, and in 2003 there was a job announcement for journalists or for the Romani desk in Kosovo’s public television. I applied and I was admitted as a journalist initially in this desk, and after two years I became editor of the program in Romani. At the moment I am the editor of the Romani program in the first and the second channel of the Radio Television of Kosovo.

BG: What do you remember most about the war…when it started?

DQ: I was not very young and I was not at the age I am now. Now I am 47. I remember 20 years ago when it started… We usually say that my generation is a generation of the war or troubles, of the poisoning in schools, when we were at school; I was in secondary school when students’ poisoning happened. There were the riots of ’81 or… We experienced all these things as children. I remember the time before the bombings in Kosovo, when old people used to say that we need to gather food because there will not be food during the bombings, and so on. I remember the day it started or one day before the bombings, we started gathering the money we had at home, we started buying some flour, some food because we thought we would be left with no food at all. We did not think there would be displacement or massive escape from Kosovo. I did not experience this war as my parent experienced World War II because they used to say that – they always used to tell us how they experienced the war at that time, that there will be bombings, this and that, and that we will stay in a basement. We tried to empty the basement from the clothes that were in there, we cleaned it, and put blankets there so that, in case there will be bombings, we could stay there. Those were the contentions of older people that we should always have an environment where we could shelter. But the contrary happened. Every time our neighborhood was attacked – because in Prizren only the neighborhood where I live was attacked – that is, attacks from the Serbian military and police. At the time when the police and military attack occurred, around 58 people died and hundreds of houses were burned.

BG: So they were murdered.

DQ: Yes, they were murdered and the houses of my neighbors were burned. Every time there were such attacks in the neighborhood we tried to leave the neighborhood because those attacks were very brutal, and we would go to a neighborhood where the community was living. We thought that it would be safer there. But there was insecurity among people. In the morning we used to escape and gather in a neighborhood. We had a house in that neighborhood, a very small house. Imagine, 3-4 families gathered in one house, staying inside, waiting what will happen, when the situation will die down. There were various opinions: they will attack us, they will not attack us, etc, etc. This was the fear of young people, and the children. We used to try to protect the children. We thought that our neighborhood would be attacked too but our houses there were very old. We would imagine being caught under the roof of the house, and such things. Always based on such contentions and conversations of older people. There was an attack – I mean, it was not an attack but young people in the neighborhood were taken to dig foxholes in the border with…

BG: Foxholes?

DQ: Yes, those were holes that were dug for the army for protection. And they used to take people on the roads; around 400 persons were taken in Prizren at the time. We tried to escape…

BG: The Serbian military?

DQ: Yes. The Serbian military and Serbian army. Actually, the Serbian police did this. They picked up people to dig these holes – the entire Prizren city knows this – and they used to enter in neighborhood. There was a moment when I went out and went in the neighborhood to see what was happening. As soon as he saw my ID card, holding it in his hand, he said to me “You have to come with us”. I saw that the neighborhood was full of people, taking my neighbors and sending them to their trucks.

BG: What were these foxholes used for?

DQ: They were used for defense, thinking that there would be attacks from Albania in Kosovo. I will tell you what happened once when Albanians were fleeing from Kosovo. In the lines that were going toward Albania and Macedonia, the Serbian military and police removed from the lines all those whom they identified as Roma or black and turned them back. Now, what their aim is not quite clear, whether they wanted to use them for labour or…I do not know. That entire neighborhood was taken, or the Albanians that had remained in Kosovo, the people that were left in Kosovo were taken on roads while they were waiting to buy bread, while buying something etc, and around 400 people were gathered in the sport’s center in Prizren, and from there they were taken to the border with Albania. The Serbian military used them to dig holes as a protection from any potential attack. But I escaped from that group, from that soldier and I hid in the roof of the house. I found a hole there from where I could see what was going on outside. I saw them open the door of my neighbors, maybe it was closed, and they opened it hitting it with their legs in order to go inside and take the people that were there. Wherever they found people who were able to work, they took them. Without any explanation.

BG: They took only the men?

DQ: Yes, only the men. This was only about men. When my family saw the trouble in the neighborhood they locked me upstairs and although they came inside they could not go upstairs, and that is how I survived from being taken along with that group. From that day, we were always afraid they would come again. Always living in fear. During the day we used to stay upstairs, at night we would go downstairs believing that they would not come at night. That was our fear.

BG: Did you have any news about the persons that were taken to work? What happened to them?

DQ: Erm, there were no news for a long time. For a long time there were not any news. Then, after a while, after 4-5 days we learned that they were safe and sound there. They did not have weapons although they had their uniform because they worked physically. They only had shovels and spades but each grouped had one or two soldiers who stayed with them as if to protect them. Such were the information that some of them brought when they came back because some of them got sick there. This was our escape from our home. While escaping form an attack, from the bombings, there was an explosion…Now, none of us know why two Roma neighborhoods in Prizren were bombed by the NATO forces. People died from that bombing and the destruction of houses or…We never received an answer on why these two neighbors where the minority lived were bombed. Now we had another fear: Will our neighborhood be bombed? Why target civilians, normal, ordinary people, people who were not involved in politics at all or in any extreme politics, I do not know. There was always this fear among us and the question why the minority was bombed, why was this done to them?

BG: Did you listen to the news? Were you aware about the crimes that were being committed?

DQ: We did, until some point there were news on the radio. We tried to listen to some radios that were online at the time, but there were not any news on television. There were news on Serbia’s television which served the news as they wanted to. But we also tried to have any sources of information from the radio “Evropa e Lirë” or to have any news on what was happening with the KLA, was there any KLA in Kosovo or were they outside the territory of Kosovo. We needed news but there were no information, we did not have any other information. We used to live as in darkness, in a darkness where there were no news, nothing… The communication was always internal, amongst us. We did not have any information by the police or the military. Apart from those attacks when they entered the neighborhoods, when they took people without any response about where they were taking them to, what was happening to those people. Only after three or four days did we get the information that they were on the border with Serbia and were opening foxholes or some sort of wall for protection from any potential attack or whatever because there were some informations that maybe Kosovo or rather the police would be attacked by NATO ground forces, always being afraid of what would happen to us, what are we. Now, at this age, at this phase, I think the minority was maltreated. Every time there were two fires, the minority was in between the two fires, ordinary people who did not have any ideology, authority over the territory or something else.

After the war, when the KLA and NATO forces entered Kosovo, when Kosovo was liberated, that fear persisted, the fear of what was going to happen with us. The entire minority was labelled us being pro-Serbs, so now the entire community would suffer the consequences of the after-war, because, allegedly, the entire minority had stolen, murdered, and God knows what else. After the war this fear did not persist, the KLA members liberated the neighborhood, but there was the fear of what we would work, how we would live. This fear was present in the minority both before and after the war. As I said, we were an entire generation that survived the poisonings in schools, the riots, etc, until the war in Kosovo was over.

BG: When you look back at the past, how big do you think is the effect of the war on you now?

DQ: As regards the minority, I am speaking now as a Roma activist, I am thinking now differently from what others thought or since I was younger at that time than I am now. Maybe the community followed people with power, but now that I think, marginalized communities, such as the Roma community in Kosovo, never have any other possibility. The community has to live, ordinary people have to maintain for themselves, they never were rich people, they never were people who had work places. People have to work and ordinary people do not have any ideology about who is in power, only who provides them a living, to survive, and then whether they work for the pro-Serbia system or pro-Kosovo or pro-Albanians, ordinary people only seek to survive and they did not care at all who is leading Kosovo, which regime or what political party is their leader. They suffer for a piece of bread, and at that time they did not think about other ideologies. Education is a big problem for them. After the war, since the 90s, a large number of the community fled Kosovo. Probably, if those people were here now, the power or community representation would be different, the needs of the community would be different, in numbers we would probably be the largest after the Albanian majority in Kosovo, and the community representation would perhaps be better. They would be intellectuals in Kosovo, those who were in leading positions at the time, maybe it would be better for the community at the moment. But, with the new authorities in Kosovo, with the participation of people from the community, maybe the war that we experienced made us more aware that we should lead marginalized communities in a more different way from the past. We need a neutral political spirit which would represent our community better in those institutions and without any contentions, as they used to have before, that the community has an ideology, but to provide them a life equal to other communities in Kosovo, so that the community they represent be satisfied with the requests presented to the institutions. The laws that we now have in Kosovo did not exist before, we were not able to ask for something. With the current laws in Kosovo, the representation of these communities would be superior if it was a decent representation, but in the most of the cases, the representation is deficient, the requests are deficient, and the rights that are asserted by law cannot be exercised. That is why I believe that the last war that this community experienced in Kosovo, made them aware and stronger so that the requests and the involvement of activists and community leaders be in a higher level than it was before the war.